Metz

|

Metz |

||

|

Motto: If we have peace inside, |

||

|

||

| Saint-Stephen cathedral in Metz, the Good Lord's lantern[2] |

||

|

|

|

| City flag | City coat of arms | |

Metz

|

||

|

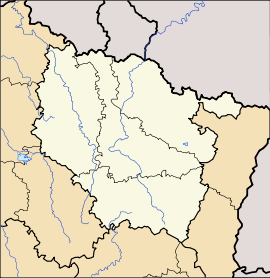

Location within Lorraine region

Metz

|

||

| Administration | ||

|---|---|---|

| Country | France | |

| Region | Lorraine | |

| Department | Moselle | |

| Arrondissement | Metz Ville | |

| Intercommunality | Metz-Métropole | |

| Mayor | Dominique Gros (PS) (2008–2014) |

|

| Statistics | ||

| Land area1 | 41.9 km2 (16.2 sq mi) | |

| Population2 | 124,500 (2005) | |

| - Ranking | 28th in France | |

| - Density | 2,971 /km2 (7,690 /sq mi) | |

| Urban area | 363 km2 (140 sq mi) (1999) | |

| - Population | 322,526 (1999) | |

| Metro area | 1,837 km2 (709 sq mi) (1999) | |

| - Population | 429,588 (1999) | |

| Time zone | CET (GMT +1) | |

| INSEE/Postal code | 57463/ 57000 | |

| Website | http://www.mairie-metz.fr/ | |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km² (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | ||

| 2 Population sans doubles comptes: residents of multiple communes (e.g., students and military personnel) only counted once. | ||

Metz (French pronunciation: [mɛs] (![]() listen); German: [ˈmɛts]) is a city in the northeast of France, capital of the Lorraine region and prefecture of the Moselle department. It is located at the confluence of the Moselle and the Seille rivers. The residents of the city are called Messin(e)(s).

listen); German: [ˈmɛts]) is a city in the northeast of France, capital of the Lorraine region and prefecture of the Moselle department. It is located at the confluence of the Moselle and the Seille rivers. The residents of the city are called Messin(e)(s).

Although historically Nancy was the capital of the duchy of Lorraine, Metz was chosen as the capital of the newly created region of Lorraine in the middle of the 20th century. An important Gallo-Roman city, ancient capital of the Austrasia kingdom, and birthplace of the Carolingian dynasty, Metz possesses a rich history over 3,000 years. Metz is historically from French culture, but because of its location, the city has been largely influenced by close German culture throughout history.

Metz is the 39th of 44 places to go in 2009 according to The New York Times.[3]

Contents |

History

Roman Divodurum Mediomatricum

In ancient times, Metz, then known as Divodurum (meaning Holy Village or Holy Fortress in Latin[4]), was the capital of the Celtic Mediomatrici, and the name of this tribe, abbreviated latter to Mettis, formed the origin of the present name. At the beginning of the Christian Era, the site was already occupied by the Romans. Metz became one of the principal towns of Gallia, more populous than Lutetia (ancestor of present-day Paris), rich thanks to its wine exports and having one of the largest amphitheaters of the country. An aqueduct of 23 km (14.29 mi) and 118 arches, extending from Gorze to Metz, was constructed in the 2nd century AD to supply the city with water, serving notably for public bathing. As a well-fortified town at the junction of several military roads, it soon grew to great importance. One of the last Roman strongholds to surrender to the Germanic tribes, it was captured by the Huns of Attila in 451, who left standing only a solitary chapel[5] and finally passed, about the end of the fifth century, into the hands of the Franks.

Early Frankish Metz

Though the first Christian churches were to be found outside the city, the existence in the fifth century of the oratory of Saint Stephen within the city walls has been fully proved. In the beginning of the seventh century the oldest monastic establishments were those of Saint Glossinde and Saint Peter. Since King Sigibert I, Metz frequently was the residence of the Merovingian kings of Austrasia and especially the reign of Queen Brunhilda reflected great splendor on the town. The town preserved the good-will of the rulers, when the Carolingians acceded to the Frankish throne, as it had long been a base of their family and one of their primal ancestors, Saint Arnuff, as well as his son Chlodulf, had been bishops of Metz. Emperor Charlemagne considered making Metz his chief residence before he finally decided in favor of Aachen.

There is evidence that the earliest western musical notation, in the form of neumes in camp aperto (without staff-lines), was created at Metz around 800, as a result of Charlemagne's desire for Frankish church musicians to retain the performance nuances used by the Roman singers.[6] In the basilica, Louis the Pious, King of the Franks, and his half-brother the Bishop Drogo were buried, and King Charles the Bald was crowned there.

Lotharingian Metz

In 843, Metz became the capital of the kingdom of Lotharingia, and several diets and councils were held there. Numerous Christian manuscripts, the product of the Metz schools of writing and painting, such as the famous Trier Ada manuscript and the Drogo Sacramentary for the personal use of a bishop of the royal house (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris), are evidence of the active intellectual lives and sumptuous patronage of Carolingian Metz. After the death of King Lothair II, the kingdom of Lotharingia, and thus Metz, was contested and changed back and forth between the eastern and the western Frankish kingdom until in 925 it finally became part of the east kingdom and subsequently the Holy Roman Empire, as a free imperial city. The increasing influence of the bishops in the city became greater when Adalbert I (928–62) obtained a share of the privileges of the counts; until the twelfth century, therefore, the history of the town is practically identical with that of the bishops.[7] Under Dietrich I of Metz (ca. 984) the monastery of Saint-Symphorien was restored. In 1039, the former Ottonian cathedral was built by Dietrich II to take the place of the Carolingian Saint-Stephen church[8]. In the spring of 1096, Metz became one of the scenes of the Rhineland massacres of non-Christians as count Emicho of Fionheim gathered followers for the First Crusade. A group of these crusaders entered Metz, forcibly converting Jewish families, and killing those who resisted baptism. 22 Jewish citizens of Metz were slaughtered.

The Commune of Metz

In the twelfth century, the burgesses began efforts to free themselves from the domination of the bishops. In 1180, the burgesses formed a close corporation, the Tredecem jurati, which were appointed as municipal representatives in 1207. The burgesses were still nominated directly by the bishop, who had also a controlling influence in the selection of the presiding officer of the board of aldermen (which originated in the eleventh century). The twenty-five representatives sent by the various parishes held an independent position; in judicial matters they helped the Tredecem jurati and formed the democratic element of the system of government. The other municipal authorities were chosen by the town aristocracy, the so-called Paraiges, i.e. the five associations whose members were selected from distinguished families to protect the interests of their relatives. The other body of burgesses, called a Commune, also appears as a Paraige from the year 1297; in the individual offices it was represented by double the number of members that each of the older five Paraiges had. Making common cause, the older family unions and the Commune found it advantageous to gradually increase the powers of the city as opposed to the bishops, and also to keep the control of the municipal government fully in their hands and out of that of the powerful growing guilds, so that until the sixteenth century Metz remained a purely aristocratic organization. In 1300, the Paraiges gained the right to fill the office of head-alderman, during the fourteenth century the right to elect the Tredecem jurati, and in 1383 the right of coining. The guilds, which during the fourteenth century had attained great independence, were completely suppressed (1383), and the last revolutionary attempt of the artisans to seize control of the city government (1405) was put down with much bloodshed.

The city had often to fight for its freedom: from 1324–27 against the dukes of Luxembourg and Lorraine, as well as against the archbishop of Trier; in 1363 and 1365 against the band of English mercenaries under Arnold of Cervola, in the fifteenth century against France and the dukes of Burgundy, who sought to annex Metz to their lands or at least wanted to exercise a protectorate. Nevertheless it maintained its independence, even though at great cost, and remained, outwardly at least, part of the German Empire, whose ruler, however, concerned himself very little with this important frontier stronghold.

French Metz

Charles IV in 1354 and 1356 held diets here, at the latter of which was promulgated the famous statute known as the Golden Bull. The town therefore felt that it occupied an almost independent position between France and Germany, and wanted most of all to evade the obligation of imperial taxes and attendance at the diet. The estrangement between it and the German States daily became wider, and finally affairs came to such a pass that in the religious and political troubles of 1552, Metz found itself in the middle of the war between Charles V and the rebellious princes. By an agreement of the German princes, Maurice of Saxony, William of Hesse, and John Albert of Mecklenburg, with Henry II of France, ratified by the French king at Chambord, Metz was formally transferred to France, the gates of the city were opened, and Henry II took possession as vicarius sacri imperii et urbis protector. Francis, Duke of Guise, commander of the garrison, restored the old fortifications and added new ones, and successfully resisted the attacks of the emperor from October to December 1552. Metz remained French.

The recognition by the empire of the surrender of Metz to France came at the conclusion of the Peace of Westphalia. By the construction of the citadel (1555–62), the new government secured itself against the citizens, who were discontented with the turn of events. Important internal changes soon took place. In place of the Paraiges stood the authority of the French king, whose representative was the governor. The head-alderman, now appointed by the governor, was replaced by a royalist mayor (1640). The aldermen were also appointed by the governor and henceforth drawn from the whole body of burgesses. In 1633, the judgeship passed to the parliament. The powers of the Tredecem jurati were also restricted, in 1634 totally abolished, and replaced by the Bailliage royal.

Among the cities of Lorraine, Metz held a prominent position during the French possession for two reasons. First, the city became one of the most important fortresses through the work of Vauban (1674) and Cormontaigne (1730). Vauban wrote to King Louis XIV: "Each one of the fortified towns of Your Majesty protects one province, Metz protects the State." Second, it became the capital of the temporal province of the Three Bishoprics of Metz, Toul, and Verdun, which France had seized (1552) and, by the Peace of Westphalia, retained. In 1633, there was created for this three bishoprics a supreme court of justice and court of administration, the Metz's parliament.

In 1681, the Chambre Royale, notorious assembly chamber, whose business it was to decide what fiefs belonged to the Three Bishoprics, which King Louis XIV claimed for France, was made a part of this parliament, which lasted, after a temporary dissolution (1771–75), until the final settlement by the Estates-General of 1789, whereupon the division of the land into departments and districts followed. Metz became the capital of the Department of Moselle, created in 1790. The revolution brought great calamities upon the city. In the campaigns of 1814 and 1815, the army of the Sixth Coalition twice besieged the city, but were unable to take the city defended by French army under command of General Durutte.

1819: A view of Metz during the Bourbon Restoration

In July 1819, the Scots born naval officer Norwich Duff visited Metz and recorded a detailed description of the town:

Metz is a large and strongly fortified town, beautifully situated on a plain at the confluence of the Moselle and Seille. It manufactures woolen goods, linen, china, paper, oil, starch and is famous for its hams, liquers, sweetmeats and artificial flowers: they also have a king's manufacture of gun powder. The government house and the promenades round it are very fine: there is also [an] immense extent of barracks for troops, a large cathedral and a theater. From the number of running ditches formed by the river there are a great many bridges: the streets like all French towns [!] are narrow and dirty and the houses high: the ground is also very uneven on which they stand. Some street performers gave us a little very tolerable music during our dinner.

Metz and the Franco-Prussian War

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, Metz was the headquarter of the Third French Army Corps under the command of General Bazaine. Through the operations of the German army, Bazaine, after the battles of Colombey, Mars-la-Tour, and Gravelotte was besieged in Metz. The German army of investment was commanded by Prince Friedrich Karl of Prussia; as the few sorties of the garrison were unable to break the German lines, Metz was forced to surrender (October 27, 1870), with the result that 6,000 French officers and 170,000 men were taken prisoners. Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche took part in the siege of Metz as a German soldier. By the Treaty of Frankfurt of 1871, Metz became a German city, and was made a most important garrison and a strong fortress. The German army decided to build a second and a third fortified line around Metz. The former fortifications on the south and east were leveled in 1898, securing space for growth and development.

20th century and modern day Metz

Following the armistice with Germany ending the First World War, the French army entered Metz in November 1918 and the city was returned to France under the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. But after the Battle of France in 1940 during the Second World War, the city was immediately annexed to the German Third Reich. Most of the Nazi dignitaries assumed it was obvious that the city of Metz, where so many German army officers were born,[9] was a German city. In 1944, the attack on the city by the U.S. Third Army faced heavy resistance from the defending German forces, and resulted in heavy casualties for both sides.[10] The Battle of Metz lasted for several weeks and the heavily fortified city of Metz was captured by the U.S. Army under the command of General George S. Patton before the end of November 1944.[11] Metz reverted to France after the war.

Nowadays, the military importance of Metz has decreased, and the city has diversified its economic base. Expansion has continued in the recent decades despite the economic crisis that besets the rest of Lorraine region. Metz is in the heart of a new economic region known as the SaarLorLux Euroregion, and combines the culture and economic aspects of this unique region in Europe. Since the 1970s, the city has developed its university and overall infrastructure for the European Greater Region. The Metz's technopole is another example of the economic revival of Metz and its region. The technopole, a high-tech park spread over 180 ha (444.79 acres) specialized in information technology, was established in 1983 and has attracted over 200 companies, 4,000 employees and 4,500 students. World-class academic institutions such as Arts et Métiers ParisTech, Georgia Tech and Supélec along with established companies including ProConsultant, SFR and TDF are located at the technopole.

In 2010, Metz opened a branch of the Parisian Pompidou centre, the Centre Pompidou-Metz, inaugurated by the president of the French Republic, Nicolas Sarkozy, on May 12, 2010. He stated that "the Lorraine region has suffered greatly in recent decades from restructuring, transfers, changes, the textile and steel industries, the mines, the military (...) In this remarkable architecture gesture, we will from now on be able to take hold of the renaissance of Metz and the renaissance of Lorraine.[12]" Indeed, in addition of the arrival of the high-speed rail connections in 2007 and the Pompidou centre in 2010, the municipality launched urban renewal plans (e.g., edification of the modern Amphithéatre district, reconversion of Metz's extensive military facilities); important infrastructure projects (e.g., edification of Mercy high-tech hospital, refurbishment of squares, public ways, and Saint-Symphorien stadium, improvement of public transportation); ambitious cultural and educational programs (e.g., construction of a new popular music venue, creation of a veterinary school, establishment of the Lorraine-University along with Nancy); and economic and industrial development (e.g., extension and creation of a second technopole).

Cityscape

The city is famous for its yellow limestone architecture, due to the extensive use of the Jaumont stone, and for its nickname The Green City. A basin of urban ecology, pioneered under the leadership of people like Jean-Marie Pelt, Metz boasts over 25 m2 (270 sq ft) of open ground per inhabitant. Metz possesses also one of the largest urban-conservation area (French: Secteur Sauvegardé) in France covering 101.5 ha (250.81 acres). In order to reduce the effects of pollution and for the convenience of pedestrians, the city's historic downtown displays one of the largest commercial, pedestrian areas in France.

Administrative division

The city of Metz is divided into different administrative divisions:

- Patrotte and Metz Nord (harbour zone)

- Devant-lès-Ponts and Les Iles (opera house, Protestant Temple Neuf, Paul Verlaine University, the marina) [13]

- Metz centre and Ancienne ville, including different historic districts such as the Centre-Ville [14], Ste Croix [15], Outre-Seille [16], and l'Esplanade [17]

- Nouvelle ville or German Imperial District (railway station, Central Post Office, Ste-Therèse-de-l'Enfant-Jesus church) [18]

- Sablon (Pompidou centre, arena, Seille park)

- Plantières/Queuleu (Queuleu fort)

- Bellecroix

- Vallières

- Borny and Grigy (technopole)

- La Grange-aux-Bois (congress centre, Mercy hospital and Mercy château)

- Magny

Civilian architecture

Metz is home to a mishmash of architectural layers, witnessing its millennium history at the crossroad of different cultures.[19] Thus, from its Gallo-Roman past, the city conserves vestiges of the thermae (in the basement of Metz's museums), parts of the aqueduct and Saint-Pierre-aux-Nonnains basilica (former Roman gymnasium). The Saint-Louis square with its arcades, where currency changers gathered, remains, with a Knights Templar's chapel, a major symbol of the High Medieval heritage of the city. The Gothic cathedral, churches, Hôtels, and two remarkable municipal granaries are depicting the Late Middle Ages.

Two examples of Renaissance architecture can bee seen with the House of Heads (French: Maison des Têtes) and with the Burtaigne Hôtel from the 16th century. The Enlightenment is represented by buildings of the Petit-Saulcy island, the opera house and the prefecture palace built by Jacques Oger, and the courthouse built by Charles-Louis Clérisseau in 1776. Also, the city hall and buildings surrounding the town square (named Place d'Armes) are works of Jacques-François Blondel, awarded by the Royal Academy of Architecture to redesign the center of Metz in 1755.

The German Imperial District, or New City (French: Ville Nouvelle), was built during the first annexation of Metz by Otto von Bismarck into the German Empire. In order to germanify the city, Emperor Wilhelm II decided the creation of a new district shaped by a distinctive blend of Germanic architecture, including Renaissance, neo-Romanesque or neo-Classical, mixed with elements of art nouveau, art deco, Alsatian and mock-Bavarian styles. Moreover, the Jaumont stone, commonly used everywhere else in the city, was replaced with stones used in the Rhineland, like pink and grey sandstone, granite and basalt. The district, thought by German architect Conrad Wahn, features noteworthy buildings including the water tower, the impressive railway station, the Central Post-Office, the Mondon square (former Imperial square), and the large Foch avenue (former Kaiser Wihelm Ring). The district was renovated during the 2000s and now displays street furniture designed by Philippe Starck and Norman Foster. In 2007, the municipality of Metz officially applied for the classification of the whole 160 ha (395.37 acres) of the district on UNESCO's World Heritage List.[20]

Modern architecture can be seen equally in the town. Thus, Sainte-Thérèse-de-l'Enfant-Jésus church, with its thin-shell structure, was built by architect Roger-Henri Expert in 1954. Moreover, the Fabert boarding high school, built by architects Roger Parisot and Paul Micholeau in 1936, and a secondary school with its chapel, the Miséricorde, built by architects Henri Drillen and Pierre Fauque in 1965, are other examples of the 20th century architecture. Subdivisions designed by architects Jean Dubuisson and Roger Gaertner (1978) can also be seen.

The Pompidou centre is a strong architecture gesture by Shigeru Ban and Jean Gastine, marking the entrance of Metz in the 21st century. The building, along with the arena by Paul Chemetov built in 2002, will be the cornerstone of the Amphitheatre district. The new district of 27 ha (66.72 acres), thought by architect and urban planner Nicolas Michelin, is currently under construction and includes the edification of a convention center and a shopping mall. The quarter already encompasses the Seille park designed by landscape architect Jacques Coulon. The urban project completion is expected to take place by 2015. Moreover, Borny district, formally designed by architect Jean Dubuisson, is currently under a large refurbishment by urban planner Bernard Reichen, and will include a concert venue, thought in music box shape by its architect Rudy Ricciotti. The completion is expected in 2012.

Military architecture

The cityscape has been largely influenced by the military architecture throughout its history. Indeed, from classical antiquity to present, the city has been successively fortified or complemented in order to receive the troops stationed there. Thus, defensive walls from different periods are still visible today and are included in garden and park design along the Moselle and Seille rivers. A medieval city gate from the 13th century, named Germans's Gate (French: Porte des Allemands), has become one of the symbols of the city. Remains of the citadel from the 16th century are still there, notably the supplies shop.

Important barracks, mostly from the 18th and 19th centuries, are spread into the city, and some of them architecturally interesting are reconverted in civilian facilities. Around the city are the extensive fortifications of Metz, that include early examples of Séré de Rivières system forts. Other forts were included into the Maginot Line defence. A hiking trail on the Mont Saint-Quentin plateau goes through former military training zone and ends with deserted military forts of the first belt, and also provides a high ground to see the city.

Culture

Entertainment and performing arts

The Opera-Theater of Metz is a 750-seat opera house on the Petit-Saulcy island. Designed by Jacques Oger and inaugurated in 1752, it is the oldest opera house working in France and one of the last possessing its own costume ateliers. The duke of Belle-Isle described it as "one of the most beautiful France's opera-theater" at his time. The Metz's opera house features annually around sixty performances, including plays, choreographies, and lyric poetry.

The Arsenal is former military building turned into an exposition and concert hall by Catalan architect Ricardo Bofill, and inaugurated by Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich in 1989. Considered as one of the most beautiful concert halls in Europe, the venue is dedicated to Classical and erudite musics, and is widely renowned for its excellent acoustics.

Located on the Sainte-Croix hill, Les Trinitaires is a multi-media arts complex housed in an ancient convent, whose vaulted cellar and chapel have been the city's prime venue for jazz music for over 45 years. Some big names of Jazz, such as American saxophonists Sonny Rollins and Archie Shepp, have performed there. The Gothic cloisters from the 13th century, used now as an open-air stage, housed once the Trinitarian Order founded by Saint John of Matha and Saint Felix of Valois. The arts complex Les Trinitaires includes also a theater, an exhibition hall, and a bar.

Moreover, a new concert venue is currently under construction. The new building, thought in a musical box shape by French architect Rudy Ricciotti, will be dedicated to popular music, e.g., rock, hip-hop, and electronic musics, and will feature recording studios. Other venues, such as the Braun hall or the Bernard-Marie Koltès theater, contribute to the choice of performing halls in Metz. The city also has a congress centre, home notably to a renown flea market every month. Finally, a large number of associations and private music bars and theaters collaborate to the entertaining life in Metz.

Interior of the opera house. |

Interior of the Classical concert venue, the Arsenal. |

Interior of the Braun theater. |

Les Trinitaires's cloisters from the 13th century, convertible into an open-air stage. |

Museums and exhibition halls

The museums of Metz, known also as The Golden Courtyard (French: La Cour d'Or) in reference to the palace of Austrasia's kings, are museums of the municipality dedicated to the history of the city. The museums are divided into four sections (history and archeological, medieval, architecture, and fine arts), and incorporate the Gallo-Roman baths, the ancient Petites-Carmes abbey, the Trinitarian church, and the Chèvremont medieval granary.

The Centre Pompidou-Metz is a museum of modern and contemporary arts, the largest temporary exhibition space outside Paris in France. The museum features exhibition from the large collection of the Pompidou centre (Europe's largest collection of 20th century art). Designed by Japanese architect Shigeru Ban and French Jean Gastine, the building is remarkable for the complex and innovative carpentry of its roof. The 77 metre (252.6 ft) central spire is a nod to the year the Pompidou center of Paris was built – 1977. The museum includes also a theater, an auditorium, and a restaurant terrace.

In addition of the Arsenal and Les Trinitaires, Metz displays other temporary exhibition and performance halls, such as former Saint-Pierre-aux-Nonnains basilica and the Knights Templar's chapel. The 49Nord-6Est, the Lorraine contemporary art deposit, is located in the Saint-Liver Hôtel, the oldest civil building of the city from the 12th century). The municipal archives, located in the Recollets cloisters, preserve and exhibit the historical records of Metz's municipality dating from medieval times to present. The Solange Bertrand foundation conserves and presents the works of the artist and organizes different art exhibitions.

Statuary of the Chèvremont medieval granary (13th C), museums of Metz. |

Saint-Livier Hôtel (12th C), Lorraine contemporary art deposit. |

Recollets cloisters (14th C), home to the municipal archives. |

Interior of the Knights Templar's chapel (13th C), temporary exhibition hall. |

Gastronomy

Different recipes, such as jam, tart, charcuterie and fruit brandy, are made from the Mirabelle plum, which is one the gastronomic symbol of the city and the land. Damson plum and rhubarb are also widely consumed. Other land's specialties include the quiche, the potée, and also the suckling pig. Metz cuisine, as well as Mosellan and Alsatian cuisine, is also known for the use in vinaigrette dressings of Melfor vinegar, a local vinegar made with the infusion of honey and plants. Local beverages include Moselle wine and Amos beer. Also, Metz is the cradle of some pastries like the Metz's tart (cheese pie-like) and the round shot of Metz (French: boulet de Metz), a ganache-stuffed biscuit coated with marzipan, caramel, and dark chocolate.

As a testimony to the Rabelaisian spirit, the Tables de Rabelais groups together thirty or so restaurants, and is a symbol of local gastronomy, serving regional products and specialities. Metz is also home to the well reputed culinary school Raymond-Mondon.

Annual events

France's second largest flea market is held one or twice a month in the congress centre of Metz. In addition, many other events are celebrated in Metz throughout the year. Here is a non-exhaustive list:

- Pilgrimage of Saint Blaise on February 3

- Funfair in May

- Été du Livre, festival of literature in June

- Bastille Day on July 14

- Macellum the first week-end of August

- Mirabelle festival in August. Every year, the city of Metz dedicates two weeks to the Mirabelle plum. In addition to open markets selling fresh prunes, mirabelle tarts, mirabelle liquor, etc... there is live music, fireworks, parties, art exhibits, a parade with floral floats and competition, and the crowning of the Mirabelle Queen and a gala of celebration [21]

- Europe's largest hot-air balloon festival in September

- European Heritage Days, the third week-end of September

- Open de Moselle in September

- Nuit Blanche in October

- Christmas market in November and December (2nd most popular in France, after Strasbourg) [22]

- Saint Nicholas parade in December. Saint Nicholas is the patron saint of the Lorraine region.

The legend of the Graoully

More details about the legend of the Graoully

The Graoully is depicted as a fearsome dragon, vanquished by the sacred powers of Metz's first bishop, Saint Clement. The Graoully quickly became a symbol of the town of Metz and can be see in numerous demonstrations of the city, since the 10th century. The French Renaissance writer François Rabelais described the Graoully's effigy during a procession of the 16th century:

It was a monstrous, hideous effigy, terrifying for small children, with eyes bigger than the stomach, and a head bigger than the rest of the body, with horrific, wide jaws and lots of teeth which were made to clash by the use of a cord, making terrible noises as if the dragon of Saint Clement was actually in Metz.—François Rabelais, The Fourth Book

Three centuries later, Paul Verlaine was also frightened as a child by the "cardboard monster". Authors from Metz tend to present the legend of the Graoully as a symbol of Christianity's victory over paganism, represented by the harmful dragon. Today, the Graoully remains one of the major symbols of Metz. A representation of the Graoully may be seen in the crypt in the cathedral. A semi-permanent sculpture of the Graoully is also suspended in mid-air on Taison street, near the cathedral. Moreover, the Graoully is shown on the heraldic emblems of Metz's football club and it is also the nickname of Metz's ice hockey team.

Education and Research

High schools

Metz is home to numerous high schools. The most notable of them is the Fabert high school, reputed for its scientific education and its classes préparatoires in mathematics. The high school incorporates parts of the Saint-Vincent abbey and the Sainte-Constante cloisters. Notable fellows of the school include Alexis de Tocqueville, Robert Schuman, Jean-Victor Poncelet, or Joachim von Ribbentrop.

University

Metz's university, Paul-Verlaine University (UPV-M), was created in 1970 as the Germans had removed any university from Metz during the Alsace-Moselle annexation. Since, the university has developed on three different main sites, Saulcy Island, Bridoux, and Metz-Technopôle. The Paul-Verlaine University enjoys a privileged position at a hub opening up to Germany and the Benelux, and has gained recognition for the development of Franco-German joint curricula. Metz's university accommodates more than 15,000 students and offers a wide range of multidisciplinary courses. The Paul-Verlaine University and other academic institutions are grouped together under Metz Campus:

- École Nationale d'Ingénieurs de Metz (ENIM)

- École Nationale Supérieure d'Arts et Métiers (ENSAM)

- École Supérieure d'Électricité (Supélec)

- École Supérieure Internationale de Commerce (ESIDEC)

- École Supérieure d'Ingénieurs des Travaux de la Construction (ESITC)

- Georgia Tech (Lorraine branch)

- École Supérieure d'Art in Metz

- Institut Régional d'Administration (IRA)

In the near future, the Paul-Verlaine University and Metz Campus should be integrated to the Lorraine-University, resulting from the federation of the Nancy-University, Metz Campus, and the National Polytechnic Institute of Lorraine. The future Lorraine-University should see the light of day in 2012.

Grandes Ecoles

Metz has other numerous public and private schools offering undergraduate and postgraduate programs, such as:

- Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers (Cnam)

- Institut Supérieur Franco-Allemand de Techniques, d'Économie et de Sciences (ISFATES)

- Institut Regional d'Administration (IRA)

- Centre d'Innovation et de Recherche franco-allemand associé de Metz (CIRAM)

- Pôle de competitivité Matériaux Innovants Produits Intelligents (MIPI)

- International Institute of Information Technology (Supinfo)

- Centre de Formation des Enseignants de la Musique (CeFEdeM de Lorraine)

Metz in arts

The Metz School (French: École de Metz) was an art movement in Metz and its region gathering around Laurent-Charles Maréchal between 1834 and 1870. Originally the term was proposed in 1845 by poet Charles Baudelaire, who appreciated the works of the artists. They were influenced by Eugène Delacroix and inspired by the medieval heritage of Metz and its romantic surroundings. The Franco-Prussian War and the annexation of the land by the Germans resulted in the dismantling of the movement. Main figures of Metz School are Laurent-Charles Maréchal, Auguste Migette, Auguste Hussenot, Louis-Théodore Devilly, Christopher Fratin, and Charles Pêtre. Their works encompass paintings, engravings, drawings, stained-glass windows, and sculptures.

Painting and printing

Monsù Desidero represented a general view of the city at the beginning of the 17th century from the high ground of the Bellecroix hill. Painter Auguste Migette created many drawings and sketches showing ancient monuments of the town, as well as monumental paintings representing the most significant moments in local history. He left his works and manuscript to the city and they are today exhibited in the museums of Metz. Also, in his work dedicated to The Beautiful Gallic Cities between the Rhine and Moselle Rivers, Albert Robida depicted in a lithography the Saint-Stephen cathedral.

View of Metz from the Bellecroix hill. By Monsù Desidero (ca. 1610). |

Saint Clement, first bishop of Metz, near ruins of the amphitheater. By Auguste Migette (ca. 1850). |

Lithography of the Saint-Stephen cathedral. By Albert Robida (1915). |

5 Open Ellipses. Urban painting of Felice Varini, Place d'Armes in 2009. |

Poetry and literature

During the German annexation of the city, French poet Paul Verlaine dedicated a poem to his hometown. Making reference to the Bazaine's treachery and to the French revanchism, he wrote:

(...) O Metz, my fateful cradle, — Metz raped and more demure — And more maiden than ever! — O city where my childhood was laughing, — O citadel with no defence — That a chief outstripped by shame, — O Mother that I loved. (...) Metz with its magnificent open countries, — Prolific undulating rivers, — Wooded hillsides, vineyards of fire; — Cathedral all in volute, — Where the wind sings as a flute, — And responding to it via the Mutte,[23] — This big voice of the good Lord! (...)—Paul Verlaine, Ode to Metz, Invectives

German author Adrienne Thomas published in 1930 a harsh criticism of the war with the First World War best-seller novel Katrin becomes a soldier (German: Die Katrin wird soldat). The text is a diaristic novel based on Thomas’s own life, describing her work at the Metz's railway mission and then as a hospital nurse during the war. The work centres upon the area around Metz, then in German territory, and not only poised between France and Germany linguistically and culturally, but very close indeed to the Western Front and on the direct line to Verdun. The text was banned in Germany during the Third Reich.[24]

Music

Metz is the seat of the National Orchestra of Lorraine. Violist, composer Alain Celo has written a piece for ensemble entitled The Graoully, Messin dragon. The piece is a musical story with narration depicting the epic fight between Saint Clement and the legendary dragon in the Roman amphitheater.

Like Adrienne Thomas, French singer Bernard Lavilliers mentioned the Metz's railway station in his work. In a song entitled Le buffet de la gare de Metz on album Le Stéphanois from 1975, he described the sort of melancholy Teutonic beauty of the building located in the German Imperial District, and the smoky, strange atmosphere of its station restaurant, where "the poetry is there, Verlaine resuscitated."

Main Sights

Religious heritage

- Saint-Stephen, Gothic cathedral (French: cathédrale Saint-Étienne) built in the 13th century. The cathedral is sometime nicknamed the Good Lord's lantern (French: la lanterne du Bon Dieu), possessing the largest expanses of stained glass windows in the world (6,500 m2 or 70,000 sq ft). The stained glass windows include works of Hermann von Münster (14th C); Théobald of Lixheim and Valentin Boush (16th C); Laurent-Charles Maréchal (19th C); Roger Bissière, Jacques Villon and Marc Chagall (20th C). Moreover, the cathedral possesses the third highest nave in France (41.41 m - 136 ft).

- Saint-Pierre-aux-Nonnains, the oldest church in France built between 380 and 395 AD as a Roman gymnasium, was converted to a Christian basilica in the 7th century. The basilica is one of the birthplace of the Roman Messin chant called later Gregorian chant.

- Saint-Maximin church, built between 12th-15th century, featuring stained glass windows of Jean Cocteau. Here, theologian Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet delivered eulogies and Paul Verlaine has been baptized.

- Notre-Dame-de-Metz church built during the 18th century in the Jesuit style and once part of a Jesuit complex. The church displays stained glass windows of Laurent-Charles Maréchal (19th C).

- Sainte-Thérèse-de-l'Enfant-Jésus church (20th C) displays stained glass windows of Nicolas Untersteller. The building has a thin-shell structure designed by architect Roger-Henri Expert, and possesses a spire in form of pilgrim's staff of 70 m (229.64 ft) high.

- Sainte-Ségolène church (13th C); Saint-Martin church (12th C, Laurent-Charles Maréchal's stained glass windows); Saint-Pierre-de-la-Citadelle church; Saint-Euchaire church; Saint-Clément church (17th C, now regional council of Lorraine); Saint-Vincent abbey (10th C)

- Recollets cloisters (14th C), housing today the municipal archives and the European Institute of Ecology

- Trinitarian Order cloisters (13th C), today a multi-media arts complex privileging the Jazz

- Chapel of the Knights Templar (13th C), built in Romanesque style and once part of Knights Templar's commandry. The chapel features important murals.

- Protestant Temple Neuf (1901–1904), neo-Romanesque church, built during the German annexation by German architect Conrad Wahn

- Temple of German Garrison (1875–1881), neo-Gothic church. It subsists only the bell tower as the church was eventually partially destroyed by Allied bombing during the Second World War.

- Synagogue (1848–1850) built in neo-Romanesque style

- Christian necropolis from the 19th century

- Jewish Cemetery of Metz-Chambière

Breastfeeding Virgin, 15th century, Saint-Martin church. |

Stained glass windows of Jean Cocteau, Saint-Maximin church. |

Ruins of Saint-Livier church from the 13th century. |

Synagogue from the 19th century. |

Civil heritage

- House of François Rabelais (12th C), including Sainte-Genest chapel (13th C)

- Paul Verlaine's native house

- Chèvremont and Antonistes granaries (respectively from 13th and 14th century)

- Saint-Livier Hôtel (12th C); Bulette Hôtel (14th C); Heu and Gargan Hôtels (15th C); Burtaigne and Gournay Hôtels (16th C); House of Heads (16th C)

- Opera house, built between 1732 and 1752 in Tuscany-influenced neo-Classical style

- Covered market, one of the oldest, most grandiose in France. Originally built in 1785 as the palace for the bishop of Metz, the French Revolution broke out before he could move in and the citizens decided to turn it into a food market.

- Centre Pompidou-Metz, built between 2006 and 2010, museum of modern and contemporary art designed by Japanese architect Shigeru Ban and his colleague Jean Gastine

Administrative heritage

- City hall and the tourism office, built by architect Jacques-François Blondel in neo-Classical style in 1755

- Hôtel de l'Intendance, prefecture palace, from the 18th century, neo-Classical style

- Courthouse, built by Charles-Louis Clérisseau in neo-Classical style during the 18th century. It is in this building, then the Governor's Palace, that the famous diner of Metz took place. During the diner organized by Broglie-Ruffec, the duke of Gloucester convinced Lafayette that the insurgent's revolt in America was in some measure justified. Lafayette wrote in his memoirs that at this dinner when he "(…) first learned of that quarrel, [his] heart was enlisted and [he] thought only of joining the colors".

- Railway station, a 300m long neo-Romanesque building designed by German architect Jurgen Kröger between 1905 and 1908. The station echoes the shape of the church (at the departure hall with the clock tower, said to be designed by the Kaiser himself) and an imperial palace (at the arrivals hall and the station restaurant), which is a recall of the religious and temporal powers of the Holy Roman emperors. In the great hallway is depicted on a stained glass window, Emperor Charlemagne sitting on his throne. The statue of the Knight Roland at the angle of the clock tower represents the imperial protection over Metz.

- Central post office, neo-Romanesque building built by German architect Ludwig Bettcher between 1908 and 1911

- Governor's palace (former General-Kommando), built by German architects Schönhals and Stolterfoth between 1902 and 1905 in neo-Flemish style. Once the residence for Emperor Wilhelm II during his visits to Metz, the mansion is used today as headquarters of the commander in charge of the North-East military region of France.

Tropaion of the Ney barrack, 1854.

Tropaion of the Ney barrack, 1854.

Military heritage

- City gates: Porte des Allemands (13th and 15th centuries), Chandellerue gate (13th C), and Serpenoise gate (19th C)

- Ruins of city walls (2nd, 13th, 15th, and 17th centuries from Louis de Cormontaigne), and supplies shop of the military citadel from the 16th century (today a luxury hotel called La Citadelle)

- Extensive fortifications of Metz. The fortifications of the first belt include early examples of Séré de Rivières system forts (Fort de Plappeville, "groupe fortifié du Mont St-Quentin").

- Fort de Queuleu (19th C), also called the Hell of Queuleu, was used by Germans as a detention and interrogation center for members of the French Resistance during Second World War.

- Former arsenal built in 1859, today a concert hall dedicated to erudite musics

- War memorial of Paul Niclausse (1935), art deco sculpture representing a mother cradling the dead body of her son

Serpenoise city gate, 19th century. |

Tower in Spirits, part of the ramparts of the 17th century. |

Former supplies shop of the Metz's citadel, 16th century. |

Fort de l'Aisne, fort belonging to the second belt of fortifications. |

Public gardens

- Esplanade garden, located close to Saint-Pierre-aux-Nonnains basilica and the Arsenal auditorium, a 9,200 m2 (140.5 sq in) French style garden, offering a commanding view on the Saint-Quentin plateau

- Seille park, located near Centre Pompidou-Metz, is a public garden designed by landscape architect Jacques Coulon

- Marina of the Plan d'Eau Saint-Symphorien

- Régates garden, an English-garden park stretching around the bottom of the ramparts of the old citadel

- Tanneurs garden, give a commanding view on the city's roofs

- botanical garden, called jardin botanique de Metz

Squares

- Place d'Armes, the town square surrounded by the city hall and the Saint-Stephen cathedral

- Chamber square and adjacent Saint-Stephen square, once used as amphitheatre-like for the Mystery plays during the Middle Ages

- Comedy square, parvise of the opera house

- General de Gaulle square, parvise of the railway station

- Human rights's parvise, parvise of the Centre Pompidou-Metz museum

- John Paul II square, parvise of the Saint-Stephen cathedral and the market hall

- Mondon square (former Imperial square), surrounded by the current chamber of commerce and the former chamber of trade

- Mazelle square, livestock marketplace during the Middle Ages

- Republic square, adjacent to the Esplanade garden and in the heart of the city, plays the role of Metz's civic center

- Saint-Louis square, medieval market square from the 13th C.

- Saint-Jacques square, located in the commercial and pedestrian historic downtown. The public square is surrounded with busy bars and pubs, whose open-air tables fill center of the square.

Sports

Clubs and sports events

Metz is home to the Football Club of Metz (FC Metz), a football association club in Ligue 2, the second division of French football. FC Metz has twice won the French Cup (in 1984 and 1988) and the French League Cup (in 1986 and 1996), and was French championship runner-up in 1998. FC Metz has also gained recognition in France and Europe for its successful youth academy, winning the Gambardella Cup 3 times (in 1981, 2001, and 2010), and producing players such as Emmanuel Adebayor, Miralem Pjanić, or Louis Saha.

Metz is also home to the Open de Moselle, an ATP World Tour 250 tournament, which takes place usually in September. The tournament is played on indoor hard courts. Frenchman Arnaud Clément won the inaugural tournament in 2003, with players Ivan Ljubičić (2005), Novak Djokovic (2006), Tommy Robredo (2007), and Gaël Monfils (2009) following his success.[25]

The Metz Handball is a Team Handball club displaying 16 wins in French Woman First League championship, 6 wins in French Women League Cup, and 4 wins in French Women F.A. Cup. French Vice World Champion Allison Pineau, who plays for the club, was elected female IHF World Handball Player in 2009.[26]

Sports infrastructures

- Saint-Symphorien stadium, a multi-purpose stadium built in 1923, home to FC Metz since the creation of the club. A project of refurbishment and extension is expected in 2012.

- Palais omnisport Les Arènes, nicknamed Les Arènes, an indoor sports arena built by architect Paul Chemetov between 2000 and 2002. It is the home venue of the Metz Handball team and the Open de Moselle men's tennis tournament.

- Saint-Symphorien indoor arena with its ice rink home to Hockey Club Metz Moselle Lorraine, Ice Hockey team club of Metz

- Plan d'Eau Saint-Symphorien, an expanse of water bulging from the Moselle river, used as a marina and for water sports

- Garden Golf of Metz-Technopôle, designed by golf course architect Robert Berthet, is a 18-holes golf course on 50 hectares located near Metz's technopole

- L'Anneau, an indoor athetics hall

Transportation

Railways

The Gare de Metz-Ville is connected to the French high speed train (TGV) network, which provides a direct rail service to Paris and the city of Luxemburg. The time from Paris (Paris East station) to Metz train station is 82 minutes. Additionally Metz is served by the Lorraine TGV train station, located at Louvigny, 25 km (16 mi)to the south of Metz, for high speed trains going to Nantes, Rennes, Lille or Bordeaux (without stopping in Paris). Lorraine TGV station is 75 minutes by train from Paris-Charles de Gaulle Airport.

Also, Metz is one of the main stations of the regional express trains systems named Métrolor. One of the main lines is the Nancy-Metz-Luxembourg line, completed by many lines going to main cities of the area.

Airport

Metz-Nancy-Lorraine Airport is the airport serving the Lorraine region. It is located in the city of Goin, at 16.5 km (10.25 mi) Metz southeast.

Motorways and local transportation

Metz is ideally located at the intersection of two major road axes: The Paris to Strasbourg motorway , itself a part of the E50 motorway connecting Paris to Prague, and the A31 motorway, which goes north to Luxembourg and south towards Nancy, Dijon and Lyon.

Local transportation in the agglomeration is carried out by buses.

Waterways

There is some significant fluvial tourism cross borders on the Rhine-Moselle system. Additionally, Metz port is the biggest cereals port in France with over 4,000,000 tons/year.

Apollo-Soyuz test project

The town of Metz has the distinction of being the location over which the first international handshake in space occurred. On July 17, 1975 an American Apollo spacecraft docked with a Soviet Soyuz spacecraft in the first joint international mission in history. When the two spacecraft docked, the hatch was opened and Commanders Thomas P. Stafford and Aleksei Leonov shook hands, which happened to occur over the town of Metz.[27]

Notable people linked to Metz

Notable people from Metz

Poet Paul Verlaine, major representative of the Symbolism. |

Ambroise Thomas, opera composer. |

Jean-Victor Poncelet, mathematician. |

Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier, first man to fly in a hot air balloon. |

Notable people linked to the city

|

International relations

Twin towns — Sister cities

Metz is a fellow member of the QuattroPole union of cities, along with Luxembourg, Saarbruecken, and Trier (neighbouring countries: Luxembourg, France, and Germany). Metz is also twinned with:

|

|

Notes

- ↑ Tout-Metz, retrieved June 2010.

Another city motto states:

Never other weapons we shall take

that those we elect;

and we claim for encouragement:

we want Freedom or death.

(French: Jamais d'aultres armes nous ne prendrons, que celles que nous élisons ; et nous disons pour réconfort : nous voulons la liberté ou la mort.) - ↑ Jolin JL (2001) La lanterne du bon dieu - la cathédrale Saint-Étienne de Metz. Éditions Serpenoise. ISBN : 2-87692-495-1

- ↑ Sharwood, Seth; Williams, Fisela. "The 44 Places to Go in 2009". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2009/01/11/travel/20090111_DESTINATIONS.html. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- ↑ Toussaint M (1948) Metz à l'époque Gallo-Romaine, Metz pp. 21-22

- ↑ History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Edward Gibbon. 1788 vol. 4 chapter 35. http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/2/5/7/1/25717/25717-h/files/733/733-h/gib3-35.htm#2HCH0001

- ↑ James Grier Ademar de Chabannes, Carolingian Musical Practices, and "Nota Romana", Journal of the American Musicological Society, Vol. 56, No. 1 (Spring, 2003), pp. 43-98, retrieved July 2007

- ↑ Newadvent.org

- ↑ KRAUS, Franz Xaver :Kunst und Altertum in Lothringen, Strasburg, 1889

- ↑ Admiral Hans Benda (1877-1951), General Arthur Kobus (1879–1945), General Günther Rüdel (1883–1950), General Joachim Degener (1883–1953), General Wilhelm Baur (1883–1964), General Hermann Schaefer (1885–1962), General Bodo Zimmermann (1886–1963), General Walther Kittel (1887–1971), General Hans von Salmuth (1888–1962), General Karl Kriebel (1888–1961), General Arthur von Briesen (1891–1981), General Eugen Müller (1891–1951), General Ernst Schreder (1892–1941), General Ludwig Bieringer (1892–1975), General Edgar Feuchtinger (1894–1960), General Kurt Haseloff (1894–1978), General Hans-Albrecht Lehmann (1894–1976), General Theodor Berkelmann (1894–1943), General Hans Leistikow (1895–1967), General Rudolf Schmundt (1896–1944), General Wilhelm Falley (1897–1944), General Julius von Bernuth (1897–1942), General Herbert Gundelach (1899–1971),General Joachim-Friedrich Lang (1899–1945), General Heinz Harmel (1906–2000), Erich von Brückner (1896–1949), Helmuth Bode (1907–1985), Johannes Mühlenkamp (1910–1986), Peter-Erich Cremer (1911–1992), Joachim Pötter (1913–1992), Ludwig Weißmüller (1915–1943), Walter Bordellé (1918–1984) among others.

- ↑ "Metz, 1944 One More River". World War Two Books. http://www.worldwartwobooks.com/product.php/5665/metz--1944-one-more-river-. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- ↑ Youtube video about the the fortifications of Metz (inner ring)

- ↑ http://www.elysee.fr/president/les-dossiers/culture/inauguration-centre-pompidou/inauguration-du-centre-pompidou-de-metz.8854.html

- ↑ Youtube video about Metz - Les Iles

- ↑ Youtube video about Metz - Centre-Ville

- ↑ Youtube video about Metz - Quartier Sainte-Croix

- ↑ Youtube video about Metz - Quartier Outre-Seille

- ↑ Youtube video about Metz - Quartier de l'Esplanade

- ↑ Youtube video about Metz - Quartier Imperial

- ↑ http://www.mairie-metz.fr/metz2/langues/english/heritage.php

- ↑ http://tourisme.mairie-metz.fr/en/metz/camaieu/imperial.php

- ↑ Youtube video about the Mirabelle festival

- ↑ Youtube video about the Christmas market in Metz

- ↑ The Mutte is the large bell of Saint-Stephen cathedral, dating from 1605.

- ↑ Brian Murdoch: Hinter die kulissen des krieges sehen: Adrienne Thomas, Evadne Price – and E. M. Remarque, 1992, Forum for Modern Language Studies, Vol. xxviii No. 1

- ↑ http://www.atpworldtour.com/Tennis/Tournaments/Metz.aspx

- ↑ http://www.ihf.info/front_content.php?idcat=173&idart=516

- ↑ NASA History: SP-4209 The Partnership: A History of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project; 17 July-The Rendesvous.

- ↑ Adrienne Thomas, le fantôme oublié de la gare de Metz. Jacques Gandebeuf. Ed Serpenoise 2009.

External links

- Official Town Council's website

- Official Agglomeration communities of Metz's website

- Historic maps

- University of Metz's website

- Metz Technopôle's website

- Metz.Online.Fr - Your guide to all web sites related to Metz

- Centre Pompidou-Metz's website

- History museums of Metz - Musées de la Cour d'Or

- Metz Opera's website

- Arsenal-Metz Concert Hall's website

- Caveau des Triniatires - multimedia arts complex's website

- National Orchestra of Lorraine's website

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed (1913). "Metz". Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed (1913). "Metz". Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company.

|

|||||